This photos show the angry mob in front of the Colonial Building on April 5, 1932. Photo courtesy of Provincial Archives NL (A2-160).

Thanks to the ELRC’s research assistant Maudie Whelan for the suggestion for this month’s topic, politics in the DNE. Politics are always a hot topic; everywhere you go, everyone has an opinion. This month, in particular, the Provincial Government has been at the forefront of the news media, social media, water cooler chats, dinner parties … one really cannot get away from the raging debates. Whatever side you’re on, even if you’re neutral, you may want to throw some local political terms into the conversation. If you use terms not listed here, please leave a comment below or send us an email!

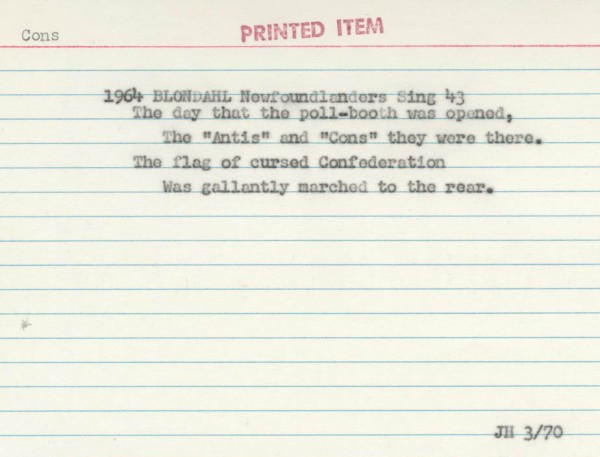

Most will be familiar with Confederation, the political union of Newfoundland and Canada. Confederate and anti-confederate, also anti and con, described the two sides. By clicking on the hyperlinked text, you can read all the entries for these terms in the DNE. The presentation of citations from the editors is interesting and perhaps makes one wonder why they might have chosen the citations listed over others given that there was certainly a large body of evidence to draw from.

Word-file for ‘con’. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

The word government itself has a number of linked compounds including government bull which can refer to an actual bull or can be a derogatory name for a government representative. There are only three word-files for this compound.

Word-file for ‘government’. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Devilskin has been used to describe a certain politician in the DNE, though the editors thoughtfully removed the name before publication.

Word-file for ‘devil’ from 1989. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Some of you may have heard the expression “there’s whigs in that”. A whig, in this sense, describes a supporter of the British political party who was opposed the Tories. The local expression is used to indicate that there is something suspicious going on. Fairity is a noun that means ‘fairness’. One speaker from Kelligrews in 1975 indicated that they believe in fairity, meaning recognizing when the opponent in a political discussion has fared well.

Word-file for ‘fairity’ from 1975. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

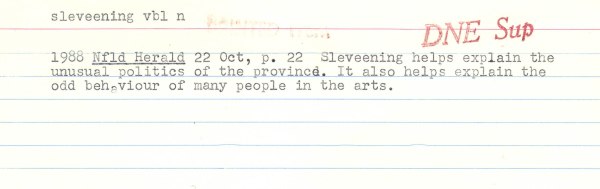

There are a multitude of words available to describe the acts of the government or a particular party or politician, but sometimes you might want a little local flavor. Sleeveen, when used as a noun, may be fairly familiar; it was one of the words Vik Adhopia picked out for a piece on the National last year (take a look by clicking here). You might be surprised to know that sleeveen can also be used as a verb or as a verbal noun. The word-file below, from the Newfoundland Herald, is the only example in the collection of this use.

Word-file for ‘sleeveening’. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

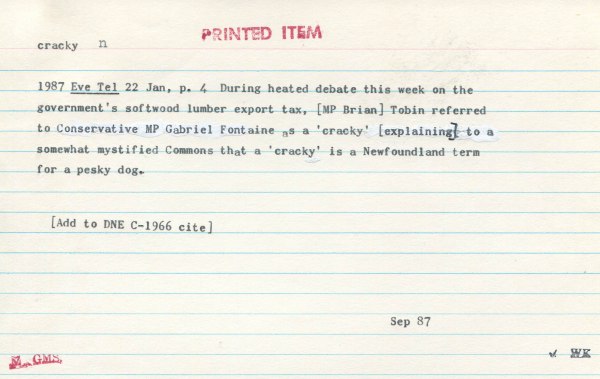

Another term that has been used to describe certain politicians is cracky as can be seen in the word-file below.

‘Cracky’ word-file. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

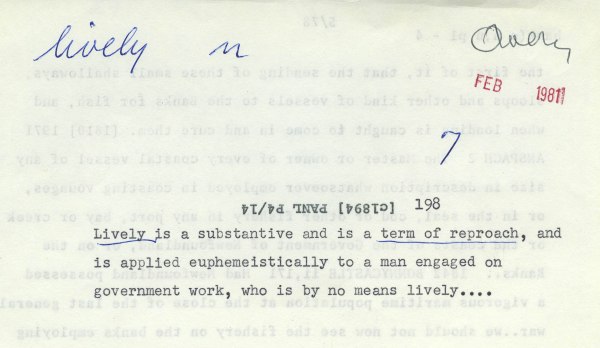

Jack-easy is a term meaning ‘lazy’ that did not make it into the DNE. In one of the two word-files for the term, it is used to describe the attitude of a government. From the queried files, there is the term lively to describe the manner in which a Government official was working. A word-file was queried when it was not clear if the usage was Newfoundland specific or not.

Word-file for ‘lively’. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

An amusing excerpt from an interview participant reflects on the 1932 Commission Government using the Irish omadhaun to express his sentiments towards said Government.

Word-file for ‘omadhaun’. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

From the withdrawn files comes an enjoyable anecdote about whether people hark or heed the government and its representatives. This file was withdrawn since this sense of hark is not particular to Newfoundland.

Word-file for ‘hark’. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

When someone misspeaks, people may say they put their foot in their mouth. In Newfoundland, the boot, or logan, is said to get caught in one’s throat. You could say, “S/he’s got more tongue than a logan” for someone who talks a lot.

Hopefully that will give you a start on your local vocabulary to describe the recent political tumults!

Both omahdaun and sleeveen were words commonly used by my parents in the house of my youth. Blackguard was another. Not always reserved for politicians. Anyone using subterfuge or manipulation could be identified as one of the above. Twillick and cornerboy had similar significance, plus another my father used I’ve never heard anywhere else – yomyock.

Thanks for these comments, Mack. The words you’ve mentioned, with the exception of yomyock, are included in the DNE. I’ve included links here for those wishing to read further about these terms. In the case of blackguard, it is interesting that religion and politics are so entangled. It is noteworthy that derogatory terms or insults can be so malleable, serving purposes outside of their typical senses such as twillick and corner boy; just one word can bring with it so many negative connotations and may be applicable to young and old. Going back to yomyock for a moment, in the queried files, we do have two word-files for yom, meaning ‘mouth’ or ‘big mouth’. One of these word-files comes from a native Irish speaker. I wonder what meaning -yock might have. I think I’ll ask a couple of Irish speakers if they are familiar with the term or something similar. I wonder where your father learned the term. You’ve provided a shining example of why lexicography and cultural preservation are vital; in one generation, although the dialect and language won’t be lost, vocabulary can be lost that could give us additional insight into where we come from and how certain areas of the province have evolved. I’ll let you know if I find out anything more on yomyock!

Suzanne

The usual rich contribution! I did wonder at “sleeven” as a verb; as a child I’d only ever heard it used as a noun, usu. singular, but never as a verbal or as a verb. “Devilskin” was directed at my brother sometimes when we were little, and “lively” is just plain fun. Nice entry!

Thanks Jacob! Before writing this entry, I had never noticed sleeveen as a verb or verbal noun in the DNE. I think it may quickly become one of my favorites though! Of course, there is much more widespread evidence for sleeveen as a noun, but the verbal usage, perhaps with its rarity, seems to cut just a little deeper. Thanks again!

Suzanne

My friend in Mobile on the Southern Shore, Virginia Dillon (who studied Irishisms in that area nearly fifty years ago and who was a child in the 1930s) tells me that, in her family, “devilskin” was always in the form “the devilskin” as in “”Isn’t that one the devilskin!” (and not as “a devilskin”). Thus her mother thought of it (and so does Virginia) as “the devil’s kin” rather than the skin of the devil.

That it has changed over time to the use of “a” (rather than “the”) is a little like the change of “Saucy as the Black” (meaning the Black Man, the devil himself) to the politically incorrect “Saucy as a black.” In both cases, a folk etymology changes the meaning.

Philip

Thanks for that information Philip and Virginia. I had a look at the word-files for “devilskin” and there are no citations from printed sources. All five usages are from interview or reported speech, not printed sources. Four of these are from St. John’s or the Avalon, and one is from Plate Cove. The term is linked in the DNE to “devil’s pelt”. Do you think that perhaps the usages might really be “devil’s kin” instead of “devilskin” but were taken to be the latter with analogy to “devil’s pelt” in mind? I was thinking that perhaps stress patterns might have shed some light on such a question but it doesn’t seem that the stress would be all that different, from a listener’s perspective anyways, especially if the speech tempo was rapid. There is also the phenomenon of word-final devoicing in Newfoundland English so it seems possible that the [z] -> [s] in “devil’s kin” so that it would sound very much like “devilskin”. Any opinion on this?

Suzanne

I think you’re right that no matter which was “first,” there would be a tendency for the two forms to fall together due to the assimilation of any [z] in that position to the voicelessness of the [k]. It could certainly have been some wag who realised the playful possibilities of exchanging the “a” for “the” (or vice-versa) and the new form would have been formed.