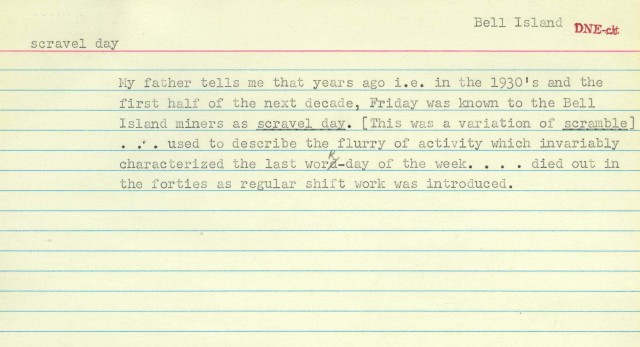

The early New Year is a time of hope, cheer, and resolution, when the months ahead sparkle with the potential of our combined good intentions. We are a society of optimistic thinkers. We are a society on vacation. But then the holiday ends and we return to our jobs. It doesn’t take long for our combined strivings for a better world to give way to our combined strivings for Friday: the final day of the workweek, or scravel day according to the Dictionary of Newfoundland English.

A word-file for scravel day, recorded in 1970. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Today, many of us return to the same jobs in the winter that we have in the fall, summer, and spring. But this was not always the case. For generations, and particularly before the industrialization of the 1950s, many people in Newfoundland and Labrador had to engage in a variety of jobs to make a year-round living. Traditional work varied from season to season and was often outdoors.

Catching and curing fish were the major summer occupations, while vegetable gardening and berry picking were also important activities. None of this was possible in the colder months, when families had to engage in other activities to secure food, fuel, and some income. Chief among these were woodcutting and trapping. Alongside contributing to the traditional household economy, these activities also added to the Newfoundland and Labrador vocabulary.

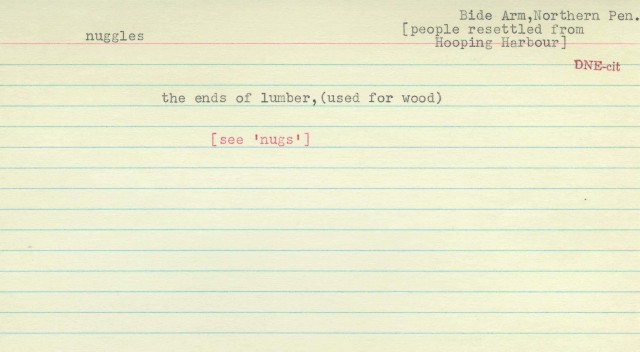

Woodcutting alone has provided us with a wealth of words. This is perhaps not surprising since wood was the main fuel many families used to heat their homes and cook their food, especially in rural areas. There are many entries in the DNE that describe the different kinds of logs, twigs, and boughs that people stockpiled. A nug, for example, is ‘a chunk of wood cut or sawn off a log for fuel’. Synonyms include: billet, birch billet, junk, and nuggles.

This word-file shows the only quotation that exists for nuggles in the DNE Collection. It was recorded in 1972. The DNE-cit stamp usually indicates that a card’s contents made it into the dictionary, but in this case the editors later decided to withdraw nuggles due to a lack of supporting evidence. Scroll to the next image to read an editor’s comment on this word. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

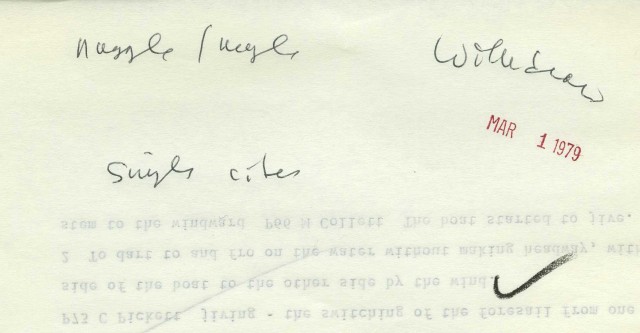

Not all word-files contain quotations; some show a commentary on a word by the dictionary’s editors. This word-file explains why the editors decided to withdraw nuggles from the DNE: “nuggle / nugle Withdraw MAR 1 1979 Single cite”. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

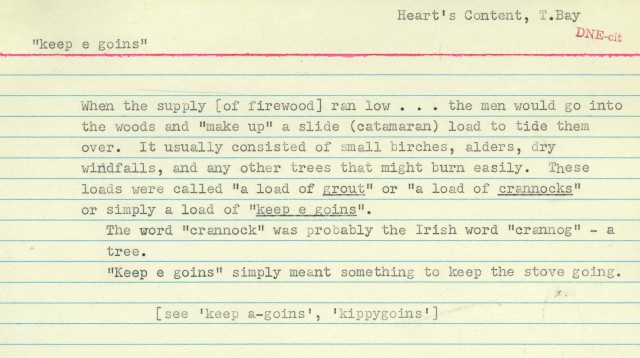

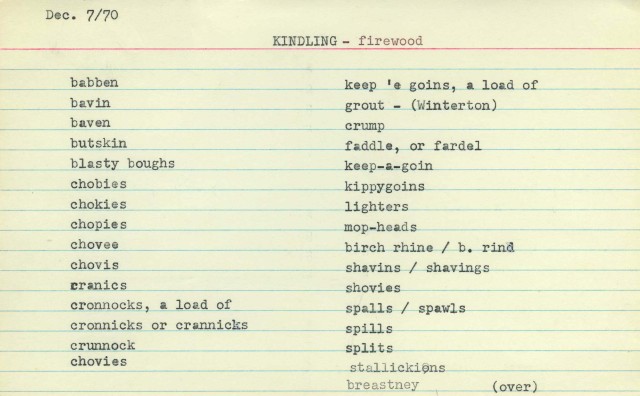

Small branches that can be gathered for fuel are known as browse (rhymes with mouse and not with boughs), while a crunnick could refer to a dried out tree root or a small sapling cut for firewood. Another term for kindling was keep a goin’s, which the DNE defines as ‘small pieces of firewood that burn readily’. This is a fitting name for the wood families quickly gathered in the wintertime to supplement their dwindling supplies of nugs and billets.

This DNE word-file (recorded in 1970) lists three variant spellings: kippygoins, keep a-goins, and keep e goins. Variant spellings exist for many words in the DNE. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Keeping an ample supply of keep a goin’s on hand was crucial to many families, who woke up each morning in freezing-cold homes with no electricity (when Newfoundland and Labrador joined Canada in 1949, only about half of all households had electricity). People learned to gather wood quickly and to distinguish between the different kinds of kindling.

To create a quick fire for your kettle, toss some blasty boughs in your wood stove – these are dead conifer branches that produce a quick crackling flame. If the boughs have no needles, they are called spray. Another kind of kindling was the bavin, mop-head, or chovy: a small piece of wood, split and whittled with a knife to give it curls at the ends. The importance that kindling once played in our society is reflected in our vocabulary – the word file below lists 31 near-synonyms, plus six more on its reverse.

Near-synonyms for kindling. Six more are listed on the reverse: jagoes, tobies, stribbins, straws, skiddles, and chaff. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

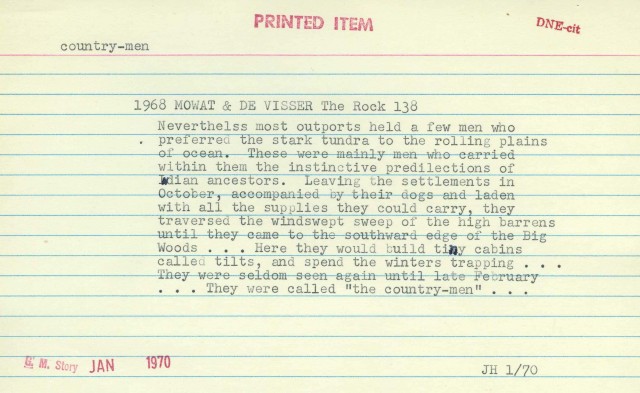

Trapping was another important, although solitary, wintertime activity. Trappers often set out alone on foot in the fall and followed their trap lines for a few months before returning home in February or March with a season’s worth of rabbit, lynx, and other furs. Trappers were known as country men, furriers, and fur catchers. In Labrador they were also called height of landers – from the phrase height of land, which the DNE defines as ‘the highest stretch of land in an area; esp the elevated plateau of western Labrador’.

A word-file for country-men from the ELRC's DNE Collection. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

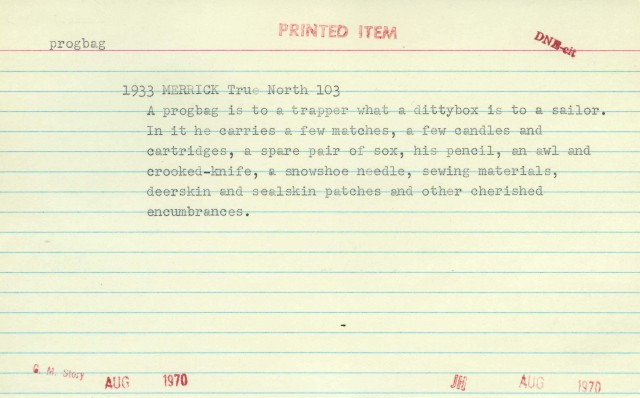

Trappers spent their days walking and their nights sleeping in tilts: temporary houses built about a half-day’s or a day’s walk apart along the trap line. With no permanent winter home, they had to live out of their suitcases, or their progbags and tabanasks. A progbag was a portable sack or container trappers used to store snacks, matches, and other small essentials. It is from the English word prog, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as: ‘Food; esp. provisions for a journey or excursion’.

A word-file for progbag. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

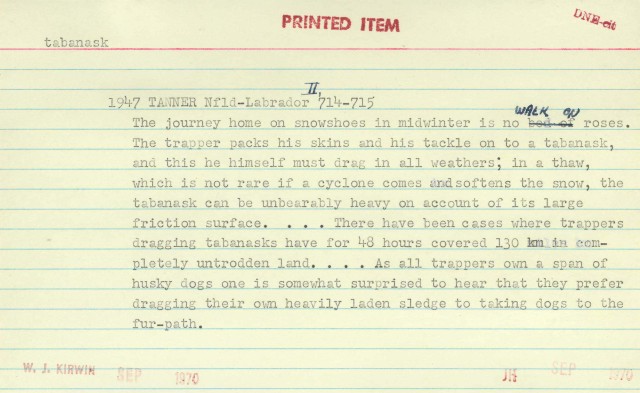

A tabanask was a sled trappers dragged behind them and loaded up with their belongings and furs. It likely entered Newfoundland and Labrador English through the Innu-aimun language spoken by Innu living in the Labrador-Quebec peninsula. This makes sense, since English-speaking trappers working in the Labrador interior would have probably been in contact with Innu in that region.

Tabanask word-file. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Bread was a staple of the trapper’s diet and could be called flummy or stove cake. Ingredients and baking methods varied, but trappers usually made this by mixing flour, baking soda, and water into a dough, which they wrapped around a stick to toast over an open fire, or laid on a stove funnel to bake slowly. Stove cake appears to have entered the Newfoundland and Labrador vocabulary by way of the Canadian North, while flummy may have originated here – there is no entry in the Oxford English Dictionary and the DNE only uses oral evidence collected from local speakers.

Trapping terms provide a useful illustration of how our history has helped to shape our vocabulary. Most of Newfoundland’s early English-speaking settlers arrived from southwest England and southeast Ireland in the 18th and 19th centuries. It therefore makes sense that the DNE contains many words of British origin, including progbag. Newfoundland English has also been influenced by the groups with whom local speakers came into language contact – including indigenous peoples and English speakers in the Canadian North. As a result, such words as tabanask and stove cake have also been added to the local lexicon.