Large icebergs, ca. 1920. Reproduced by permission of the Maritime History Archive (PF-323.025), Memorial University.

Spring is the time of icebergs in Newfoundland and Labrador. Mammoth and majestic, they drift through our waters between March and July, although June is usually the best time to see them. Most started their journey about a year earlier, after breaking away from ancient Arctic glaciers off Greenland’s west coast. Their ice may be more than 10,000 years old, but the bergs begin to melt once they move into warmer waters; it will only take a year or two for them to disappear.

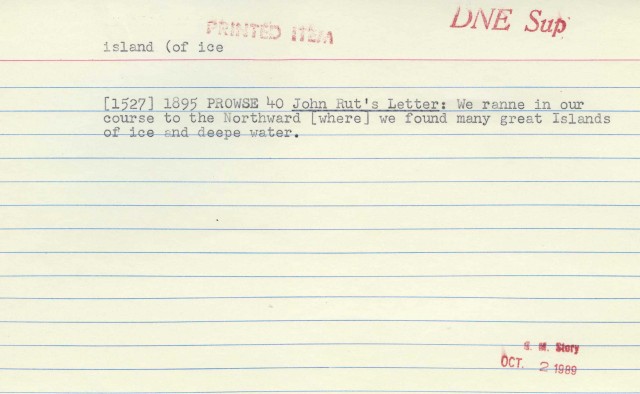

People come from all over the word to watch icebergs, a fascination they share with some of our earliest visitors. One of the oldest references to an iceberg in the Dictionary of Newfoundland English dates back to 1527, when English explorer John Rut wrote of “great Islands of ice” inhabiting our waters. The DNE lexical files indicate the phrase was still commonly used in some Newfoundland and Labrador communities by the second half of the 20th century.

This quote from English explorer John Rut is likely the earliest reference to an iceberg in the Dictionary. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Iceberg watching is not the only way spring ice has contributed to our culture and economy. Historically, Newfoundlanders and Labradorians are a seafaring people; for centuries they have depended on the often icy waters of the North Atlantic to make a living. The annual spring seal hunt in particular brought people in close contact with a wide variety of sea ice.

Sealers on the ice by their ship, n.d. Reproduced by permission of Archives and Special Collections, Memorial University.

Since the 1790s, sealers have been sailing, and later steaming, to the floes off Newfoundland’s northeast coast to hunt harp seals. Understanding the different conditions they may encounter was a matter of life and death – both for the seamen who navigated through ice-filled waters and the hunters who spent hours on the floes in search of seals. It’s not surprising that there are many words in the DNE to describe sea ice.

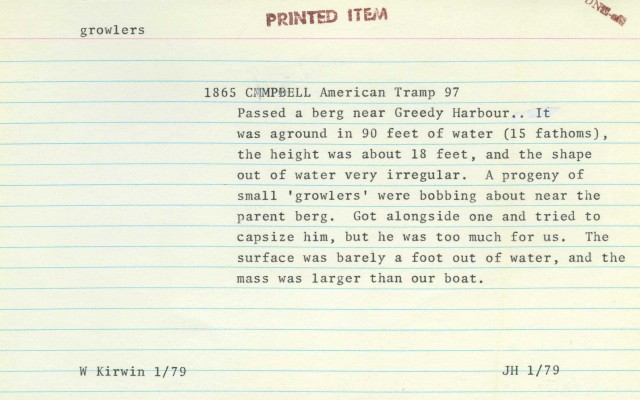

Small icebergs are particularly dangerous. Rising only a few feet out of the water, they are difficult to see, yet powerful enough to punch a hole in a ship’s hull. Among the most notorious are growlers. The earliest recorded usage in the DNE is from 1865, and the word is still used today in both the province and around the world.

The earliest recorded reference to growlers in the DNE. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

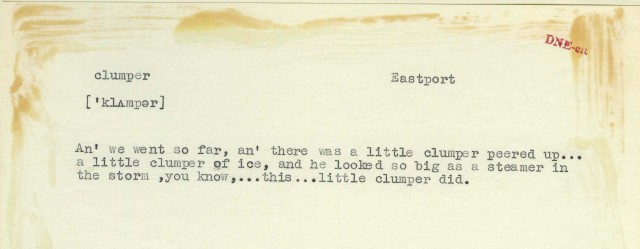

Less well known are clumper, roller, and rolling pan. The first of these is likely from the Old English clympre for ‘lump or mass’. According to the English Dialect Dictionary, clumper was being used in southwest England by the mid-1800s, where it meant ‘a lump; a heavy clod of earth’. It was likely brought to Newfoundland and Labrador by English settlers later that century.

The DNE lists five senses: 1. a small iceberg; floating pan of ice; 2. a hummock of ice in an ice-field; 3. slab of ice forced up along the shoreline; formation of ice frozen on shore from action of waves and wind; 4. a small chunk of ice or snow; and 5. clumper-anchor: iron chain with ‘jigs’ protruding at intervals, used to moor a boat to a small iceberg.

From an interview recorded in 1964. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

A roller is ‘a small iceberg that tips over easily’. This sense of the word may have originated in Newfoundland – the DNE’s earliest (and only) recorded usage is found in Philip Tocque’s 1846 publication, Wandering Thoughts, or Solitary Hours. Tocque, a teacher and clergyman from Carbonear, wrote the book while living in Bird Island Cove, Trinity Bay. The Oxford English Dictionary contains many different senses of roller, but none refers to sea ice; the same is true of the English Dialect Dictionary and the Dictionary of Canadianisms.

Rolling pan is another term that may have originated here. It means a small iceberg rocking in the sea water and, like roller, does not to appear to have ever been in widespread use. The DNE and its lexical files record only two sources, one from 1842 and the other from 1966; both works were written on the island.

Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

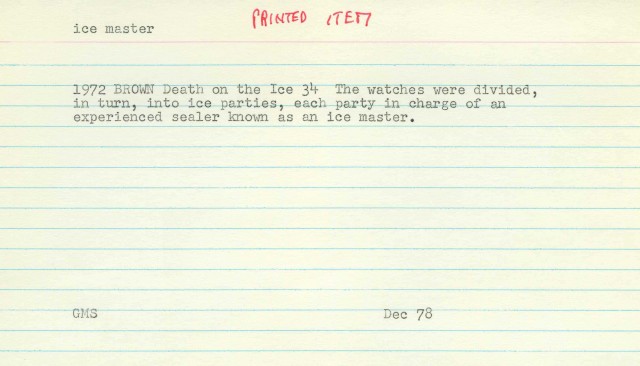

Sea ice, however, isn’t just something for ships to avoid – sometimes they have to maneuver right into it. Vessels engaged in the seal hunt had to penetrate the ice fields to find the herds. Once they did, captains ordered their crews overboard to bring back the pelts. In the 19th and early-20th centuries, sealers could spend up to twelve consecutive hours on the ice, often walking for miles over unstable ice pans. It makes sense that these men became known as ice-hunters and ice-masters – those who ventured into the floes had to be expert seamen, with expert knowledge of ice conditions.

Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

An entire vocabulary emerged around the hunt. Open your DNE to ice and you’ll find many terms: ice pilot, ice skipper, ice-master, ice captain, and ice-hunter all refer to sealers or the captains of sealing vessels. Once on the floes, sealers became an ice party, with each man carrying an ice pole (or gaff) to kill seals and help keep balance on unsteady ice pans. The hunt itself was ice-work or ice fishing, and the annual spring trip north an ice voyage, made aboard ice skiffs or ice boats.

Some of these terms, such as ice hunter, may have originated here, while others, such as ice pole and ice pilot, were also used in the Canadian North.

Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Harp seals give birth on relatively smooth pans of ice, which sealers have at various times called gardens, whelping ice, and seal meadows. These terms appear either to have originated here, or to be of special local significance. The Oxford English Dictionary (online, under meadow n.) defines seal-meadows as ‘N. Amer. (chiefly Newfoundland). An area of sea ice on which seals haul out in large numbers. rare.’

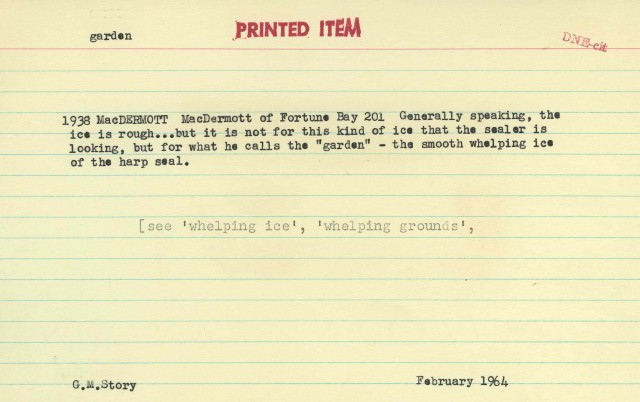

Its entry for whelping ice cites three quotations, all from Newfoundland or Labrador. The Dictionary of Canadianisms also describes the phrase as a Newfoundland one. None of the OED’s many senses for garden refers to ice or seals, and the sense may be unique to the province, although not widespread. The DNE provides a single quotation, from the 1938 publication MacDermott of Fortune Bay, Told by Himself.

The Dictionary’s only quotation, and only word-file, for this sense of garden. Reproduced by permission of the English Language Research Centre, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

Those of us who inhabit gardens of a greener variety will likely not get to see glacial ice up close. But if you ever do find a small chunk floating close to shore, it may be worth your while to break off a piece. Once melted, it makes a lovely drink – either cold or boiled for a mug of pinnacle tea.